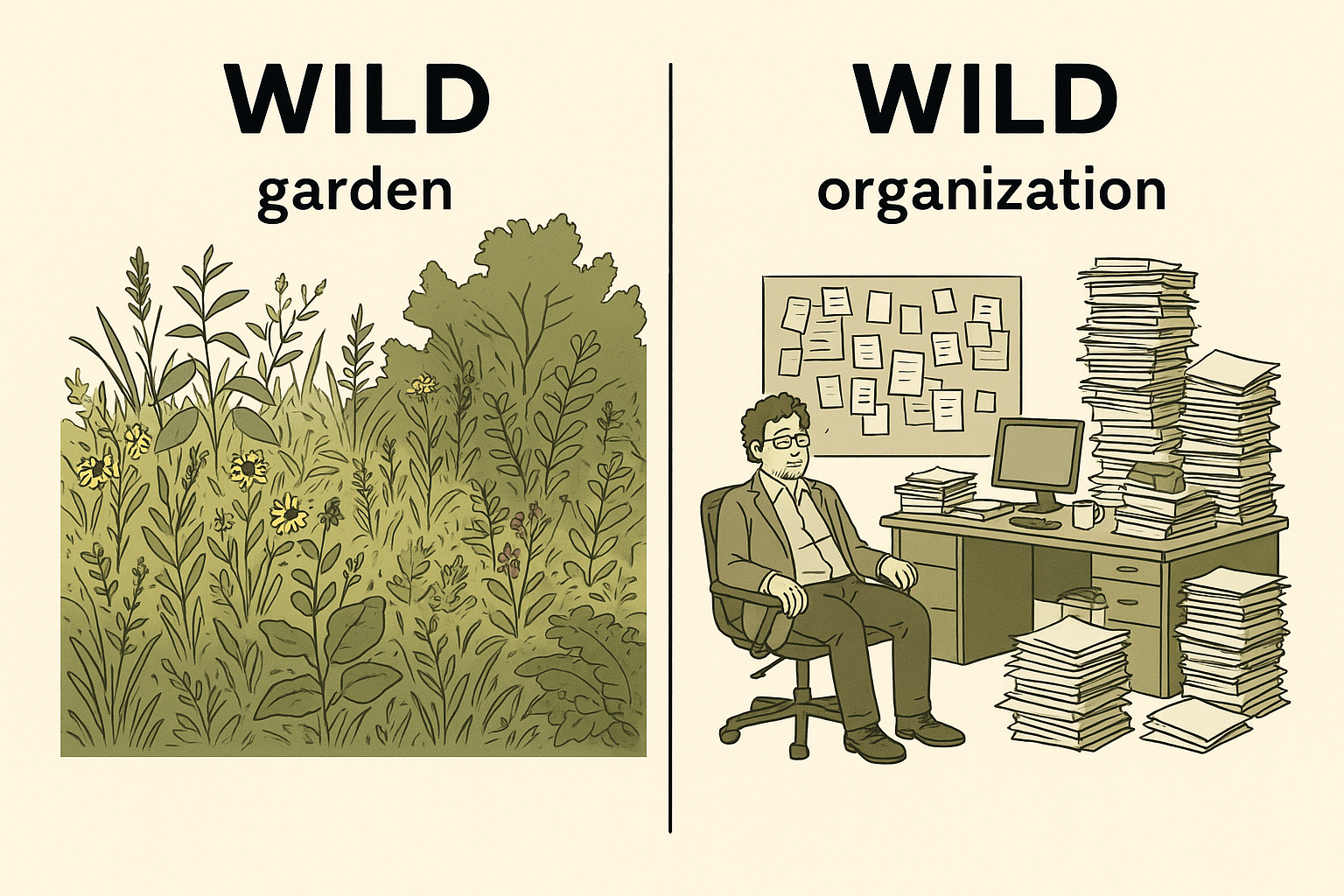

This post was born out of a thoughtful exchange with a mindful and innovative colleague — someone genuinely committed to exploring new ways of organizing, strategizing, and innovating. We talked about complexity, emergence, nature, and letting strategy evolve like weeds in a garden. On the surface, I understood the appeal. But something in me pushed back. That rejection wasn’t about resisting complexity. It was about a metaphor-driven misunderstanding: the idea that if we simply let things grow, better systems will inevitably emerge. This skips over a critical truth — complex systems still need equally complex ways of being steered, governed, and cultivated. Emergence isn’t enough. Without a matching evolution in the way we regulate and support those systems, “letting things grow” leads not to innovation, but to drift.

In Henry Mintzberg’s 2018 post, “Need a Strategy? Let Them Grow Like Weeds in the Garden,” he argues that organizations should allow strategy to emerge from the grassroots rather than being planned from above. The metaphor is clear and persuasive: centralized control feels stifling in the face of complexity, while a looser, emergent approach allows room for novelty, diversity, and adaptation. In a similar spirit, Eric Gilliam, in his 2024 and 2025 writings on BBN-style organizations, champions the power of scrappy, open-ended teams pushing the frontiers of knowledge through fluid collaboration and mission-aligned curiosity.

These ideas are powerful, and they speak to something that often feels missing in rigid institutional systems. But there’s a risk in romanticizing emergence without understanding what actually makes nature adaptive in the first place. In ecosystems, diversity and resilience are real, but they are not unregulated. Nature doesn’t work because it’s chaotic — it works because it’s full of feedback: intricate relationships, evolutionary pressure, mutual dependencies, and time-tested mechanisms for maintaining balance.

Human systems are fundamentally different. Nature doesn’t set goals or compress timelines. It doesn’t attempt to eliminate suffering, achieve carbon neutrality, or educate every child. But humans do. We define explicit values, work under constraints, and build institutions to deliver outcomes (see the UN Sustainable Development Goals). That makes our systems both artificial and intentional — and it means that if we remove structure without designing new adaptive mechanisms to replace it, we don’t get emergence. We get entropy.

How it’s actually done

This is where W. Ross Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety becomes essential. In his foundational 1958 insight, Ashby argued that any system trying to regulate another must have as much internal variety — that is, as many states or possible responses — as the system it wants to control. In plain terms, complexity must be met with complexity. A simple controller cannot effectively regulate a complex system. The consequence is that when we increase system complexity — say, by “letting things grow” in an organization — we must also increase the complexity of our governance mechanisms. Otherwise, we simply remove scaffolding and hope the building stands.

Importantly, applying Ashby’s Law doesn’t mean returning to rigid bureaucracies or top-down command systems. It means building governance and organizational models that can handle complexity without becoming brittle or overbearing. Such systems are designed not to issue orders from above, but to enable coordinated action from within. For example, instead of one central office dictating how every team works, you might set shared goals, define core interfaces, and then let teams choose their own tools, rhythms, and local adaptations — as long as they feed into the broader mission.

A complexity-capable system is one that can balance multiple priorities at once: technical feasibility, ethical alignment, user needs, long-term outcomes. It does this by embedding feedback loops — real-time data, reflective learning cycles, or user-informed decision points — that allow the system to adjust course without needing constant external correction. In practice, this might look like:

– Clear shared direction (e.g., a well-articulated mission or theory of change)

– Minimal but well-designed coordination mechanisms (e.g., recurring synthesis reviews, shared APIs or knowledge protocols)

– Empowered nodes (e.g., teams or units that make decisions locally, informed by their context)

– Rapid feedback and reflection (e.g., internal retrospectives, testbeds, advisory groups, horizon scanning)

– Evolutionary accountability (e.g., systems that are evaluated not just on deliverables but on how they learn and adapt)

This kind of structure is not loose or informal. It is disciplined in a different way — through shared principles, intelligent scaffolding, and iterative learning.

Junior Talent

In all this, there’s an often-overlooked dimension that deserves attention: the role of junior talent. Allowing for emergent strategy and grassroots innovation isn’t just about process. It’s also about people — especially the people who are just entering the system. When organizations create space for bottom-up innovation, they’re not only opening the door to new ideas, they’re creating the conditions for new leaders to emerge. Junior members are often closest to new technologies, fresh perspectives, and the lived experience of the system’s current pain points. When empowered, these individuals don’t just contribute — they grow into future stewards of the organization’s evolution.

This matters deeply. Because systems that fail to engage the next generation are not truly adaptive. They are only temporarily stable. By contrast, systems that cultivate junior talent as co-creators of strategy — and give them the space to experiment, learn, and lead — build long-term resilience. The values that empowered them early on are often the ones they carry forward. These are the kinds of cultural loops that enable real institutional renewal.

Take Home

So yes, let strategies emerge. Let innovation grow at the edges. Let your organizational garden surprise you. But don’t forget that real gardens need more than sunlight and soil. They need stewards. They need people who understand when to prune, when to plant, when to step back, and when to intervene. A garden without care doesn’t become a jungle of beauty. It becomes overrun.

Complexity is not an excuse to avoid control. It is a call to evolve it. And the next generation — if we empower them well — may be the very ones who build the control systems we’ve been missing.

No responses yet